Beijing, June 6, 2016:Â Concerns about harmful emissions have resulted in construction being halted at a number of incineration plants around the country. Now, experts are claiming the country will drown under a deluge of garbage if the situation doesn’t change soon.

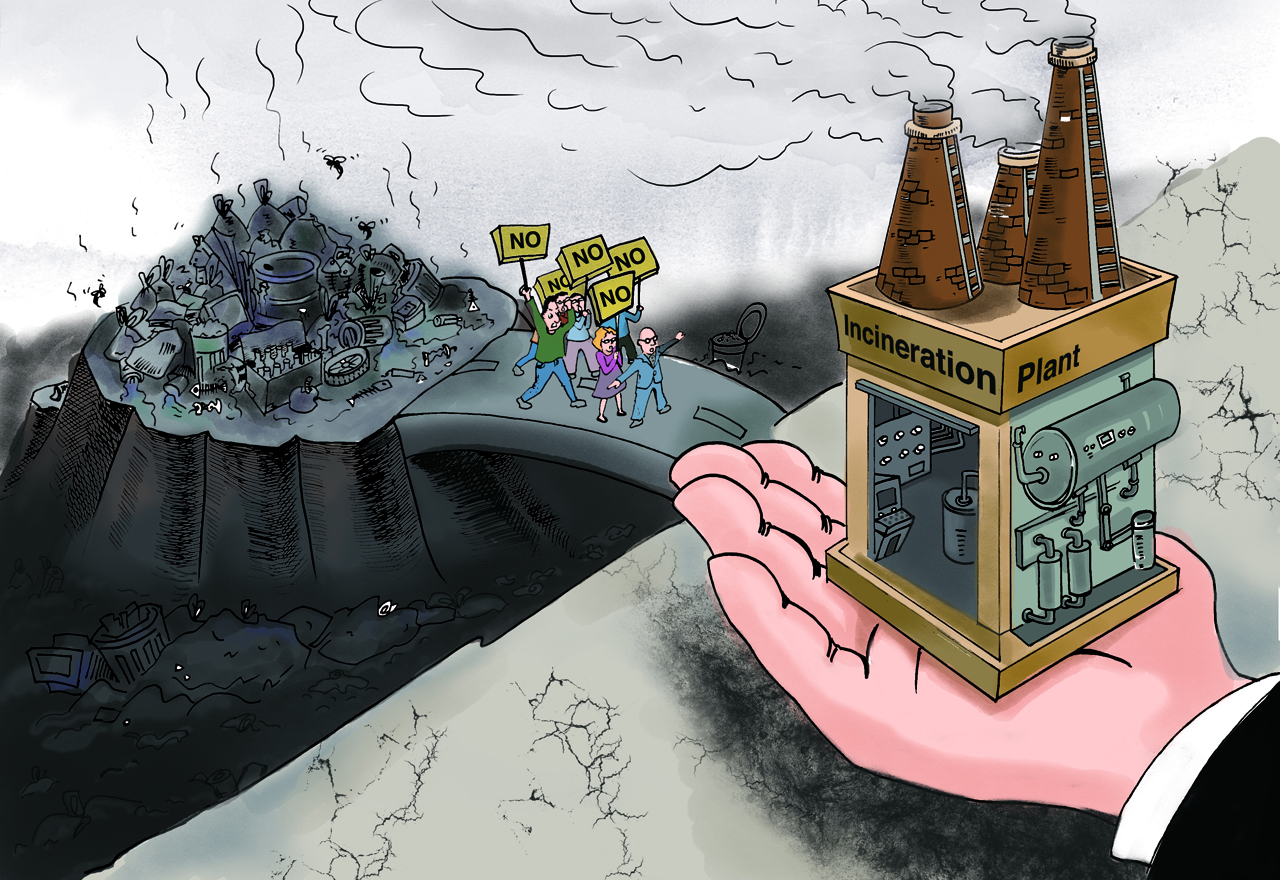

China is facing a mountain of unprocessed household waste after public protests disrupted the construction of incineration facilities, and as landfill sites reach capacity, according to experts.

In 2014, 179 million metric tons of household waste was collected nationwide, according to data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics. Meanwhile, statements released by the central government say the volume of waste is expected to grow at between 7 and 10 percent every year in large cities, such as Beijing.

Public protests

On April 21, the government of Haiyan county in the eastern province of Zhejiang, announced that it was cancelling construction of a new waste incineration project in response to two days of public protests. However, it also released a statement calling for public support, saying the new plant was urgently needed to prevent a buildup of waste that could result in widespread pollution.

Residents of the county, which is administered by Hangzhou city, voiced concerns about the potential health risks from emissions via online forums and through direct representations to the government. Some protesters even blocked roads and attacked and injured a number of police officers and government officials.

Most of Haiyan’s household waste used to be processed at incineration plants in other counties, but late last year the plants were so overloaded that the operators refused to burn waste from outside their own area, leaving Haiyan’s landfill sites close to full.

“Without new facilities to deal with the waste, the county will soon see severe pollution from a flood of waste,” the government’s statement said.

The problem isn’t just confined to Haiyan, though. Several areas of the countryï¼including Beijing and the provinces of Guangdong and Hainanï¼have seen protests against new incineration plants, despite the ever-rising volume of waste as a result of urban expansion.

At present, the three main methods of disposing of household waste are landfill sites, incineration and composting.

However, experts say it’s not feasible to bury such enormous amounts of waste in landfillsï¼the most widely used methodï¼partly because most of them are nearly full and partly because of a lack of land to build more.

Incineration has become the most popular treatment because the plants require less land than waste-burial sites, the materials are easy to deal with once burned and the incineration process generates heat and power.

Those advantages saw the number of incineration plants rise to 188 in 2014 from 104 in 2010, according to government data. Meanwhile, a survey conducted by the Power Generation Branch of the China Association of Circular Economy, an industry association in Beijing, estimated that the number of facilities has doubled in the past six years, reaching 225 by May.

‘Not in my backyard’ Â In the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), the central government has encouraged the construction of waste incineration plants to protect the environment. However, public opinion is divided. Some people have objected to the construction of new plants, even though they acknowledge the need for themï¼the “not in my backyard” syndromeï¼while others seem unfazed.

Guo Gaoyun, secretary-general of the Power Generation Branch, who has conducted research into incinerator operations for many years, said the key factors are the implementation of emissions standards, strict supervision and smooth, timely communications.

“It’s easy to set stringent standards, but it’s never easy to implement them strictly,” he said, adding that the public perception is that many plants fail to adhere to the standards and governments don’t supervise them adequately.

An incineration plant run by China Everbright International has been operating in Jianhu, a village in Changzhou, Jiangsu, since 2008. It deals with waste from five large residential communities and villages scattered across the neighbourhood, with a population of more than 100,000.

During the planning stage, a number of residents voiced concerns about possible pollution from the incinerator, said Liao Guoyong, the plant’s deputy manager, who added that the city government invited local residents to visit the plant and get a clearer picture of its operations.

“Our plant is open to the public, giving people access to emissions data. We also hold quarterly meetings to answer any questions people may have,” said Liao, during a welcoming address for a group of researchers from the All-China Environment Federation.

According to a survey conducted by the plant, 56.5 per cent of respondents (mostly local residents) said their confidence in the facility had risen and they now support its work.

Liao said the plant has not received a single complaint about environmental damage or air pollution in the eight years since operations began.

However, Wu Yongxin, a senior engineer at an incineration plant in Ningbo city, Zhejiang, said it’s not enough to release emissions-monitoring data, and it’s far more important to maintain strict controls and adopt the best emissions-reduction technologies.

Public concerns about health risks and pollution caused by incineration have focused on dioxins, the malodorous gases and dust discharged during burning and wastewater from leachates (liquid that has percolated through a solid object and contains traces of the original material), Wu said.

Dioxins are highly toxic, persistent environmental pollutants that can cause cancers, result in reproductive and developmental problems, and also damage the immune system.

To control pollution, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development released tough guidelinesï¼the Standard for Pollution Control on Municipal Solid Waste Incinerationï¼on July 1, 2014.

The standard adheres to the strictest European standards, especially those related to the emission of dioxins.

“In addition, dioxin emissions from incinerators cannot be compared with the large amounts of dioxins emitted by chemical plants, which cause far more air pollution,” said Yan Weifu, an engineer with Everbright’s technology department.

Yan’s opinion was echoed by a number of experts and officials.

Xu Haiyun, chief engineer at the China Urban Construction Design and Research Institute, said that if governments implemented the national standards rigorously, the volume of dioxins discharged would not pose a threat to people’s health.

There were no indications of noxious gases or dust when China Daily visited plants in four cities in East China: Ningbo in Zhejiangï¼which is home to the largest number of incineration facilities in the countryï¼plus Changzhou, Nanjing and Suqian, all in Jiangsu.

A better way to win public support for incineration projects would be for governments at all levels to strengthen supervision and communicate fully with the public, Xu said.

Lu Huangzhong, deputy head of the Suqian environmental protection bureau, told members of the Trans-Century Tour of Chinese Environmental Protection, an inspection team led by the national legislative branches on environmental protection, that all the monitoring data for the city’s incineration plants goes online directly and the bureau also conducts regular field monitoring.

“The monitoring of incineration plants has and will always be a priority for the public and for environmental protection,” Lu said.

Construction resumes  For the public to accept existing incineration plants, local governments will have to adopt the methods used in Suqian and strengthen supervision to ensure that emissions meet national standards, experts said.

Faced with the problem of a rapidly rising amount of household waste, many cities will have to improve communications with the public so that aborted incineration projects can be restarted, they added.

In 2013, more than 3,000 residents of Boluo, a village in Huizhou city, Guangdong, objected to the construction of an incineration plant, even though the government had already introduced stringent protective measures.

The village and city governments regularly demonstrated the measures they employed to protect drinking water, undertake regular monitoring and maintain employment levels. Eventually, the campaign overcame local objections, leading to construction being completed last year, and the start of a pilot operation, according to a statement released by the local government.

In Beijing, construction of the Asuwei Incineration Plant resumed at the end of 2014, after being suspending for five years because of opposition from local residents.

The resumption won public support after the municipal government promised strict supervision and supplementary facilities to reduce pollution. In addition, the residents were relocated.

After seeing the anti-pollution measures in the 2014 plan, Huang Yishan, who protested against the Asuwei plant in 2009, changed his opinion and is now confident the facility will not cause pollution.

A number of other stalled incineration projects will resume soon, despite objections, because they are urgently needed and their construction will boost economic growth.

“Governments should shoulder more responsibility for the situation and supervise operations to ensure they keep their promise to protect the environment and human health,” said Guo, from the Power Generation Branch.

By Zheng Jinran