After being denied access to temples, some Dalits began tattooing the name of the Hindu god Ram on their face and body.

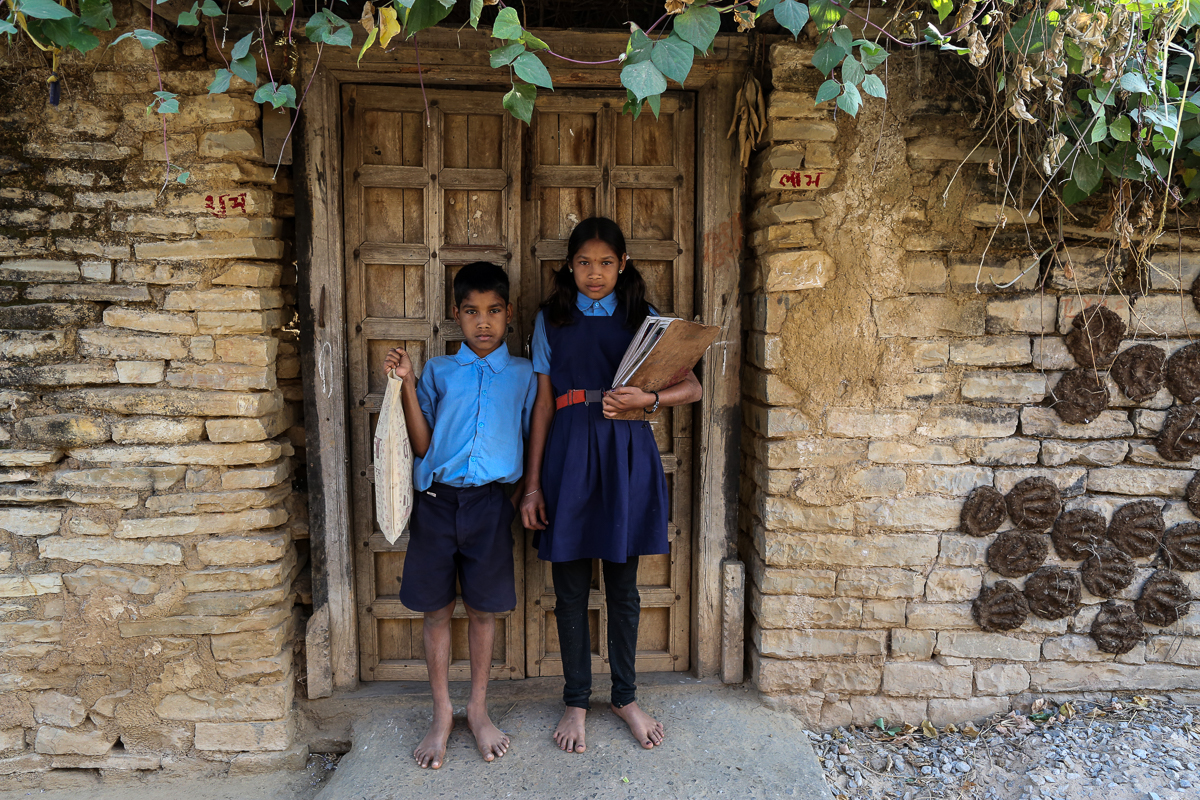

Around 250km from Raipur, the capital of the Indian state of Chhattisgarh, are some villages where small, often dilapidated mud homes, their walls painted in shades of blue, line broken roads.

Most of the people who live here are Dalits – the least privileged in the Indian caste system.

Dhani Ram Sonwani is a 60-year-old farmer who lives in the village of Charpora. “The underprivliged castes in the caste system were oppressed by the privileged castes, which made their lives hell,” he explains as he sits outside his run-down home. “We were called names such as chamar and achhoot [untouchables]. Our ancestors were treated worse than animals and weren’t even allowed to enter temples.”

It is this last point that explains the tattoos on Sonwani’s face and body. They are the name of the Hindu god Ram, and many other older residents of his village and the neighbouring ones have similar markings.

They are followers of Ramnami Samaj, a religious movement founded in the 1890s by a Dalit Ram devotee called Parshu Ram Bhardwaj, who was denied entry to a temple in one of these villages in Chhattisgarh.

“Who needs a temple when we have the name of god written on us?” says Sonwani. “God is everywhere and not just in temples.

“There is a temple near our village and no one from our community has ever entered that temple,” Sonwani adds. “We have no idea which god’s idol is housed in that temple.”

He says that Dalits are not discriminated against to the same extent that they were before but that “there is still a long way to go” until the inequalities of the caste system are eradicated.

The tradition no longer takes place but, in the past, members of the community were typically tattooed after marriage, which would usually take place some time between the ages of 11 and 14. Because the process could be extremely painful, the tattoos – which were usually administered by women using an ink made from soot and water – would be done at intervals.

Seventy-five-year-old Samund Bai lives in the village of Baday Sipat and remembers being tattooed shortly after she married at the age of 13.

“My husband had tattooed his entire body and asked me to get the name of Ram tattooed on my face as it was part of our culture and religion,” she recalls. “The pain that came with it was a nightmare. I could not eat or drink for six months.”

Younger followers of Ramnami Samaj are no longer tattooed, with many believing that they hold them back by revealing their caste in a country where Vibhishan Patray, the president of the Jan Jagran Samiti (People’s Awakening Society) NGO, says caste-based “discrimination is still prevalent in many parts”.

Samund Bai remembers attempting to visit a temple with her husband during the 1980s and being turned away because their tattoos gave away their caste. “It was heartbreaking when the priest of the temple refused to let us in,” she says. “It was then that we decided we will not tattoo our children, even though they follow the Ramnami movement.”

By Showkat ShafiÂ