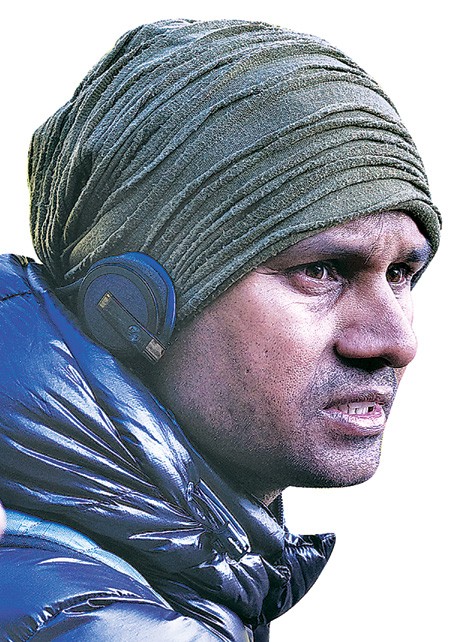

With tales rooted in post-insurgency Nepal and with narratives that push the limits of traditional Kollywood storytelling, Deepak Rauniyar has quickly emerged as a leading filmmaker ushering in a new wave of Nepali cinema. After breaking into the scene with his first feature film, Highway (2012), Rauniyar’s second movie, Seto Surya (White Sun) has gone on to win critical acclaim and accolades in the international film circuit this year. Now gearing up for its Nepal premier at KIMFF 2016, the moviemaker hopes that White Sun will receive a similar response at home. In this interview with Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga, Rauniyar talks about the inspirations behind his new film and the role movies play in edifying history. Excerpts:

White Sun will be seeing its Nepal premier at KIMFF 2016, are there plans afoot to take it to the wider audiences?

Yes, right after the KIMFF premiere, White Sun will be released in some 18 screens, in eight cities, by Popcorn Pictures–Kathmandu, Pokhara, Butwal, Nepalgunj, Narayanghat, Hetauda, Itahari and Birtamode.

The movie has already been critically acclaimed at several film festivals this year. Did you always plan to take the movie to the international circuit before its Nepal unveiling?

Yes, I did. Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Toronto are the World Cup, Olympics (so to speak) for filmmakers. It doesn’t matter where you’re from or how small or big your film industry is, if you want exposure and prestige for your film, international film festivals are the way to go. Influential directors like Steven Spielberg and Woody Allen still seek festival premieres for their films. In fact, both of their new films premiered at Cannes Film Festival earlier this year.

As a Nepali filmmaker, another reason to seek international exposure is funding. We have no government support like in India, China or Europe. So, we have to look elsewhere. With White Sun, we’ve been extremely fortunate. During the development stage the film was selected for the Cannes Film Festival’s L’Atlier, Cinefondation program, and won grants from Doha Film Institute in Qatar, Tribeca Film Institute, Jerome Foundation and Asian Cultural Council in the US, Hubert Bals Fund and Netherlands Film fund.

Was the movie specifically made with the global audiences in mind?

No. When I’m writing a film I’m not thinking about the audience. My films are not driven by market trends. Sex, comedy or item numbers is not my priority. I choose a subject that I strongly believe in, a story which I feel no one will tell if I don’t. Then I live with the consequences, even though they might be unpleasant.

Tell us about the inspiration behind the movie and how the story came together.

In early 2009, Asha, my wife, was directing a promotional documentary for the Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Center in Kavre. I helped edit her film. A heated conversation between an ex-policeman and a former Maoist guerrilla, both spinally injured, caught my attention. I met them later and interviewed them. That was the first inspiration for White Sun story. Then Highway, my first feature film, happened and White Sun took a back seat. Later in 2012, after Highway released in Nepal, I started to think about my next project. The political landscape had changed in these three years and I had to reconceive the film. I approached David Barker, editor of Highway, if he would co-write the script with me. He agreed. Together we developed the script for White Sun and completed it after four years.

The movie deals with a very recent and deeply relevant subject for Nepal, but so far mainstream Nepali movies, for the large part, have skirted away from themes from the Maoist insurgency. Why as a filmmaker was it important for you to make a movie about the subject, and what role do you think movies play in edifying history?

I was 17 when the Maoist-led war started. 22 years later, for good or bad, the country is still going through a political process as a result of the same war. How could I ignore it? Still, one thing I did not want to do is make another sad, hopeless film about a bloody war. I was more interested to explore the aftermath of the war.

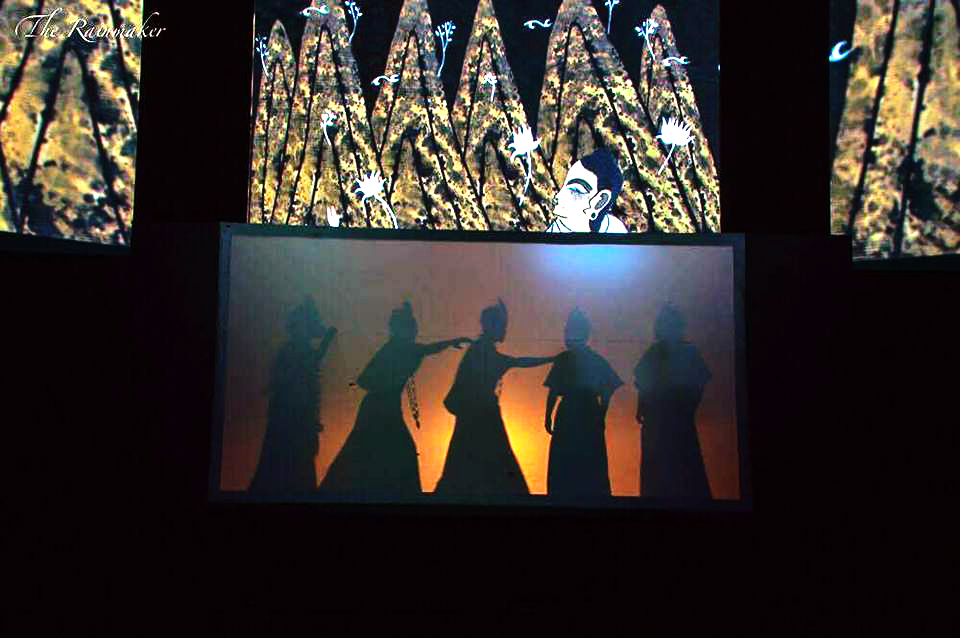

The film takes place around the time of the announcement of the constitution in late 2015, so the title refers to the white sun on our national flag. The dead body at the beginning of the film is a metaphor for the old constitution and the king’s regime, overthrown after the 10-year civil war. Just as the country struggled to establish a new government and constitution, the film’s characters struggle to get the old man’s corpse out of the house. No matter how cumbersome, they choose to stick to their old beliefs, thus making life harder for themselves. The situation and arguments in White Sun represent our mindset. The characters in the film represent the past, present and future generation and how children, even before understanding the complexities of caste and class, suffer from archaic beliefs thrust upon them.

Your last movie, Highway, also tackled another relevant social motif, national strikes. Your works are rooted in reality. For you, what role do films play in a society, particularly one in transition like ours?

Films are not just a medium for entertainment, they are also the strongest form of art. Films tend to have a direct or indirect impact on our lives. Look around us and we can see the influence of Bollywood. So if we can consciously steer this medium, films can help build the kind of society we want to see. In a time of divide, cinema can be used as a medium to connect and help us understand each other.

The Nepali movie industry and the stories that are being brought to the silver screen are evolving rapidly. Where do you see the Nepali movie industry, both commercial and independent, in the future?

King Mahendra brought a man from India in 1965 to direct and produce films to promote his regime. An actual film industry only began to flourish in Nepal post-1990’s People’s Movement when the media became more open. Until only a few years ago, Nepali films were based on the popular Bollywood-style formula: a hero and villain, couple of fights, song and dance. But this has changed a lot over the last couple of years. Today we make more than 100 films a year and our filmmaking has more variation. Digital technology has empowered young filmmakers. Who would have imagined an anti-hero like Dayahang Rai (who plays Chandra/Agni in the film), would go on to become such a popular mainstream hero. We are still a developing industry but there is growing hope as a new wave of cinema has emerged.

But where is the sign of government support, funding, subsidy, anything? Formal co-production is still not encouraged and there’s no actual cooperation even with India with whom we share an open border.

What project are you working on next?

I’ve begun to develop my third feature film, which is currently titled Raja. But it’s still in its early stages. I can probably announce it around January next year.