Kathmandu, March 25, 2017: I sometimes wonder how I became a rebel,” wonders award-winning Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen, who was in Kathmandu recently for a talk programme. Nasreen has written more than 40 books including poetry, essays, novels and autobiography series.

It is all the more of a wonder as she describes herself as “a very shy girl who used to read books. I didn’t go out. I didn’t have many friends. I was busy all the time reading books. I wasn’t very outspoken”.

Nasreen is known for her strong and hard-hitting writing on women’s oppression and criticism of religion and patriarchal society. As a result multiple fatwas calling for her death were issued, while her books were banned in Bangladesh, ultimately resulting in her exile.

“When I look back, when I see that I did a lot of things, I cannot imagine I have actually done or could do so many things,” this 54-year-old writer divulges adding, “Some things I did for the first time. I rented an apartment in 90s to live alone — that was for the first time in Bangladesh that a woman was living alone. I started it and I feel proud of it. I broke a lot of taboos — I didn’t wear dupatta as a teenager surprising the boys on streets. I fell in love and I decided to marry, which was not arranged. Then I realised that the man was not right, so I divorced. I started to live alone in my late 20s.”

Nasreen started writing and publishing poems when she was 13 inspired by her brothers who “used to write, edit and publish poems in literary magazines which we used to call Little Magazine in late 70s”. She later published poetry books like Shikore Bipul Khudha (Hunger in the Roots) and Nirbashito Bahire Ontore (Banished Without and Within) in the 80’s followed by many other poetry books, essay collections, novels, short stories and autobiographies and their translations.

She gained more popularity when she started writing columns for “women’s rights and freedom from my personal experience: what happened to me and what I saw on the streets, what happened to other women inside their homes and how they are treated by their husbands — from my personal experience. Those columns were very popular because nobody wrote that way; my columns were very strong and hard hitting against the patriarchal system and anti-women tradition, customs and culture. I spared none. Women started liking and reading my columns”.

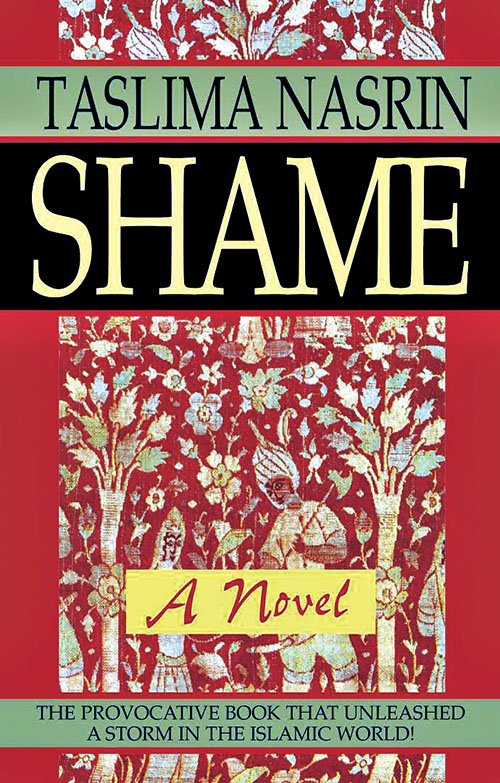

But her views didn’t sit well with the Muslim fundamentalists. The Lajja author shares, “They issued a fatwa against me and started processions and demonstrations with hundreds of thousands of people demanding my execution. That was a very bad time.”

This former gynaecologist used to go to work on a rickshaw. One time she came face-to-face with a procession. “I was lucky that I survived. There were 50,000 people and my rickshaw was just in front of them. I asked the rickshaw puller to take an alley because if they recognised me, they would have killed me,” she says of her narrow escape in 1993.

In 1994, the Bangladesh government filed a case against her on “charges of hurting religious feelings” which sent her into hiding. “I was staying from one house to another because police and fundamentalists were looking for me. At that time I was scared. I thought that I may be killed. I never thought I would survive,” admits Nasreen, who left her country the same year.

Despite the madness and threats, she kept going. “I want to do myself proud. If I bow down and I surrender to them and go to a peaceful country so that I can be safe, I feel it would be very selfish because I write for rights, human and women rights. It gives some meaning to my life. Also I get so much support and love from the oppressed people — this gives me strength,” she shares.

And she writes “whatever I have learnt and believe in”, not to create controversy. “It is them who don’t believe in it are creating controversy. I am saying the correct things like women should be treated equally. I have not said this to create controversy. It should be,” she asserts.

If her opinions and views have hurt sensitive people and their sentiments, shouldn’t she draw a line?

“Why should I have to care about that sensitive people’s sentiments? They should manage their hearts. We all are hurt listening to something, but we have an in-built mechanism to manage the heart. Nobody has the right to live their life without being offended. Everybody has the right to offend others. It is freedom of expression. Without offending others, there is no meaning of freedom of expression,” she opines.

As such Nasreen “does not draw a line” and believes nobody should either, otherwise there is no meaning of freedom of expression.

Though exiled, nothing has stopped her from expressing her views freely.

“I have been trying to go back to my country but I am not allowed to enter. It is sad but I don’t give up. I continue writing. Even though I am a European citizen, I chose to live in India. After 10 years of living in the West, I moved to

India that once banned me,” she admits.

As she writes in one of the Indian languages, she decided to live in India. Also “it is very challenging for me to live in India. I am a green carder holder of America and a European citizen. I could have lived there peacefully. But I want to change society and challenge a lot of things. I want to challenge the patriarchal system. It is best for me to live in a country where I know the language and also I can contribute to society”.

Her writings

Nasreen mostly writes about women alongside anti-women rituals, traditions and cultures. She also writes about secularism, secular society and human rights, against religious suppression and religious fanaticism.

“Women are oppressed. They don’t have equal rights, they are not treated as humans; they don’t have freedom. I have seen that in my society; I was harassed because I was a girl,” she says of why she writes about women. And also “because I have seen how women suffer because of religious law and system. Religion is patriarchal. Women are not considered equal humans under the religious system”.

Nasreen firmly believes that women should have the rightsto continue their education and get financial independence, very important for women’s right.

Unlike many girls in her society, Nasreen grew up in “secular environment” where her father encouraged her for education. And she is thankful to her father who made her to study medicine which she loved. “I am really grateful to my father as science helped me a lot because I am free of superstitions and all kinds of religious beliefs — science made me a rational person,” she explains describing herself as “never a religious but curious child”.

For woman to be equal, it should start at home. “Women will never get equal rights outside home if they don’t have it at home. They have to get equal rights everywhere and be respected as equal beings, rather than be respected as a weaker being like ‘let her go first’ or ‘give her seat’,” she opines.

She has written voraciously against the system and for change, but she does not call herself an activist. When she became a renowned feminist writer in Bangladesh, many women’s organisations asked her to join them, but she didn’t.

“I don’t care about the government and big people. I don’t care what happens to me. If someone is in an organisation, they become limited. They have to please the government, they cannot also be so angry against fanatics,” she points out. “If I write alone, I don’t have to care about anything. If I am involved, then those leaders will always ask me not to write this and not to write that. So, I want to be free when I write. I believe in free thought. And I work alone.”

Her strength

“Writing is life for me. I cannot imagine living life without writing. It gives me so much strength,” she shares. And she believes her work is a prescription for society.

Many women go to her or buy her books — “that made me realise women are reading my books”.

“I get feedback from women. They say that they were forced to stop their education, and now are continuing with their studies; they were housewives, they have struggled and now have a job; they were abused by their husbands, now they are divorced — all these they say they did because they got strength after reading my book. This gives me idea that people are changing,” she says.

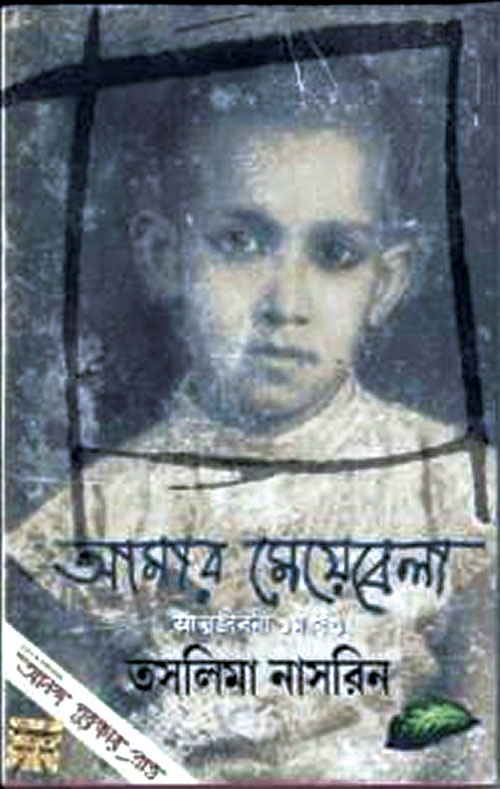

Her famous books include novel Lajja (1993) and biographies Amar Meyebela (My Girlhood) and Ka (Speak Up).

When she was in Nepal, many girls and women went to her to “take photographs. Before they used to come for autographs, now come they come for photographs. Time has changed”.

Nasreen, who is working on a new novel, expresses, “I didn’t know I was so popular in Nepal. So I love that. So many girls and women, and also men, said that they read my books even though I don’t know who published my books in Nepali,” she says adding, “They never got my permission for translation and they never gave me the royalty. But it is okay if the translation is good. I don’t know from where they translated, from Bengali or Hindi. But if the translation is good, I have no problems if they don’t pay me royalty. At least the readers can read what I wrote.”

By Jessica Rai