Everyone knows the Moomins – but how many know of the brave life and challenging paintings of their creator, Tove Jansson? Cath Pound finds out more.

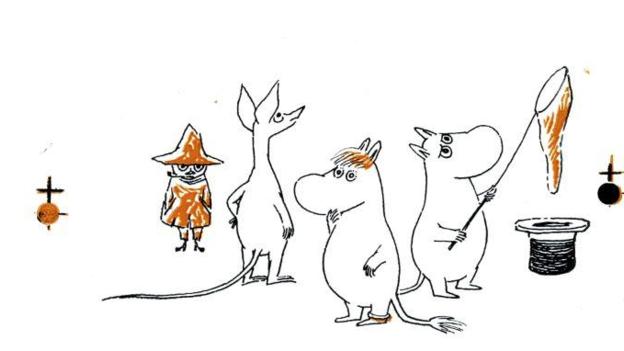

Tove Jansson is known and loved around the world as the creator of the rotund children’s characters, the Moomins. However she always considered herself first and foremost a painter and the fact that this side of her work was often ignored caused her great frustration and sadness. Adventures in Moominland at the Southbank Centre in London and another exhibition of her art, currently in Stockholm and arriving at the Dulwich Picture Gallery next year, allow us to see both sides of her extensive oeuvre.  Although vastly different in approach, both exhibitions emphasize the tolerance which imbues her work and which derives from the courageous way she chose to live her life, refusing to submit to the restrictive norms of contemporary Finnish society.

The daughter of Finnish sculptor Viktor Jansson and his Swedish artist wife Signe Hammarsten-Jansson, known as Ham, Tove Jansson grew up in an environment where art, work and life were inseparable. By the age of 14 her work was already appearing in print and she soon followed her mother to the satirical magazine Garm. At art school, where her early work had a mystical, fairytale quality to it, she was considered a bright and promising student. The self-portraits she painted in the 1930s and ’40s reveal her development as an artist and, thinks art historian Tuula Karjalainen, are among her strongest works.

If World War Two had ended differently, the consequences for Jansson would have been fatal

The war years were traumatic for Jansson but also provided a great stimulus to create. She had been mocking Hitler in the pages of Garm since as early 1935 but the war heightened her satirical bite. Her cartoons reveal a pathetic and ridiculous clown behind the monster who threatened Europe. As Finland had entered into an alliance with Germany in 1940, her work caused consternation among the authorities and the magazine came perilously close to being charged with insulting the head of a friendly state. Her courage in challenging public opinion cannot be underestimated. If the war had ended differently the consequences for her would have been fatal.

Finnish lines

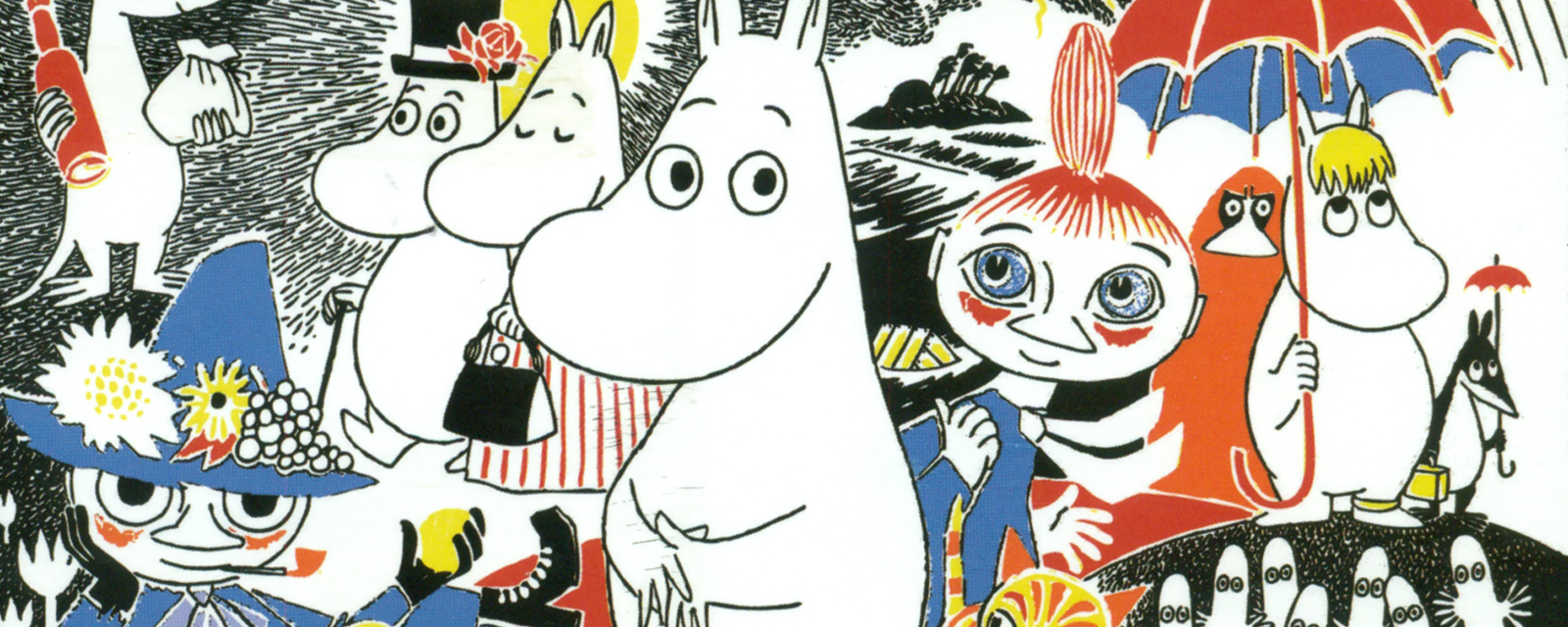

It was the horrors of that time that also served as inspiration for the first Moomin books. “She had to create alternatives to the world she was living in,†says Jansson biographer Boel Westin. Not that this alternative was any less bleak. The Moomins and The Great Flood contains images of refugees searching for their relatives while Comet in Moominland, completed just after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, sees the residents of Moominvalley facing possible annihilation from a comet hurtling towards earth. Her characters are granted happy endings but all the same, “they’re quite exceptional for children’s books at that time,†says Westin.

At last I feel that in love I can experience myself as a woman – Tove Jansson

The end of war brought joy in many forms, not least that of the theatre director Vivica Bandler, with whom Jansson fell madly in love. To discover that she was attracted to women was something of a surprise to Jansson but she confided to friends that, “at last I feel that in love I can experience myself as a woman.†Unable to be as open as she would have liked about the affair – homosexuality was illegal in Finland at the time and not decriminalised until 1971 – Joansson instead included herself and her lover in the third of the Moomin books, Finn Family Moomintroll, as Thingumy and Bob.

These two characters arrive in Moominvalley speaking a strange language that no one else can understand and carrying a suitcase containing a magnificent ruby which they have stolen from the evil Groke. Westin sees the ruby as a metaphor for their love: the most important thing is for them to open their suitcase and reveal its contents to Moominvalley.

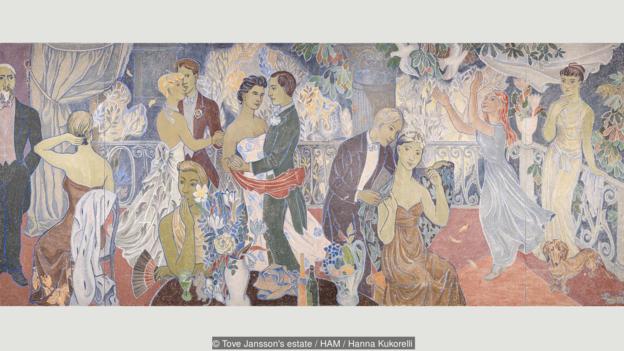

Jansson went on to depict her lover in one of the monumental murals she painted for Helsinki Town Hall. Vivica, easily recognisable to their immediate circle, stands resplendent in its centre, dressed in a stunning evening gown. Jansson herself sits in the foreground, a Moomin at her elbow, staring defiantly out at the viewer. Like Thingumy and Bob she is displaying their love for all the world to see.

Ultimately the affair was to prove short lived but the couple remained lifelong friends.

Joy is further evident in The Book About Moomin, Mymble and Little My. A riot of colour, shape and form, it is heavily influenced by Matisse and a work of art in its own right. Both Mymble and Little My are the offspring of the older Mymble, a gloriously polyamorous character who lives for pleasure and to procreate. Her name derives from the Swedish slang mymla, meaning to make love, and Jansson’s circle delightfully used ‘mymble’ to refer to a lover of either sex.

‘Personal story’

Moominmania really began to take off in the 1950s, thanks in large part to the comic strips produced for London’s Evening News, which were distributed worldwide. Their popularity was to prove a double-edged sword, however. They provided a much needed regular income, but the demands of producing a weekly strip meant that Jansson’s time for painting was severely restricted.

It was a situation that could not continue and at the end of the 1950s Jansson said goodbye to the comic strips. The strength to make such a life-changing decision came from her new partner Tuulikki Pietilä, known as Tuuti, immortalised as Too-Ticky in Moominland Midwinter, a book which Paul Denton, a producer at the London’s Southbank Centre where Jansson’s works are currently on show, sees as their personal love story. Moomin wakes up in winter while the rest of the family are hibernating. Initially afraid, he meets Too-ticky who teaches him how to live in this new environment “and it’s much the same as Tuuti did with Jansson, teaching her a new way to live and love,†he says.

In 1959 Jansson, painted another self-portrait. She called it Beginner. Her expression is calm and determined, her gaze directed at the easel. It is signed Jansson in a bid to separate her from the Tove of Moomin fame. Belatedly she tried her hand with abstraction but, “as a storyteller she had difficulties as an abstract artist,†says Tuula Karjalainen. “She paints landscapes that are quite abstract anyway – the sea, waves or storms –  and if the painting is abstract from the start she adds more figurative elements.â€

If there was one thing that made her truly sad later on in life it was that people only saw the Moomins in her – Sophia Jansson

Jansson returned to the Moomins in 1965 with Moominpappa at Sea, which deals with her troubled relationship with her father. Â Feeling as if he is not needed, Moominpappa behaves with uncharacteristic chauvinism in whisking his family off to an uninhabited island to prove his worth. Moominmamma, who Jansson had always said was based on Ham, is so homesick that she paints countless pictures of Moominvalley, which miraculously come to life.

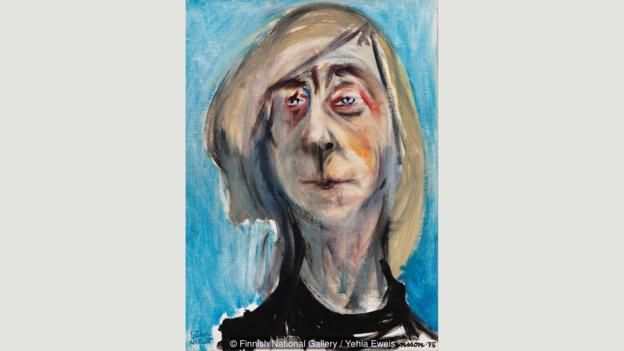

Throughout the 1970s Jansson largely devoted herself to writing for adults but on a trip to Paris in 1975 she picked up her brushes again and painted what Karjalainen thinks are two of her finest paintings. An unflattering self portrait showing herself with sagging skin and red rimmed eyes and a portrait of Tuuti, seated at her easel surrounded by colour and light.

Jansson’s niece Sophia says that, “if there was one thing that made her truly sad later on in life it was that people only saw the Moomins in her,†but Karjalainen finds it equally sad that, “she did not fully understand what remarkable art her illustrations and cartoons were.†Fortunately, we now have the ideal opportunity to appreciate both sides of this multi-talented and truly remarkable woman.

By Cath Pound